The Cornerstone of Modern Dentistry: Supporting Patients' Behavioral Changes

Article written by Filippo Graziani, DDS, PhD, Professor of Periodontology at the University of Pisa, Italy, and Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Introduction

The treatment of periodontitis and gum diseases in general is becoming an increasingly important objective within the dental profession. It is undeniable that a rising awareness of the tremendous effects, both at a local and systemic level, and the significant widespread prevalence of the disease are calling our profession daily to reinforce strategies for detection, diagnosis, and successful treatment.

Yet, the treatment of gum diseases is somewhat a unicum within the dental field. In fact, successful treatment does not rely solely on technical skills and manual dexterity. Rather, the capability to successfully build a sequential process of different steps encompassing a diverse set of abilities, i.e., from health communication skills to fine surgical micro-movement, is the foundation of the contemporary treatment of periodontitis.

Among the various moments of treatment, it is the extremely diverse and indefinite Stage I (patient’s behavioural changes and health-promoting skill adoption) that often captures my highest level of concentration.

Periodontitis is a multifactorial disease, and the pathogenetic mechanisms are deeply intertwined with the development of a gingival inflammatory reaction, within a susceptible host, to a dental plaque dysbiosis. The understanding of this has profoundly shaped the treatment of the disease in which, in the last 50 years, the main focus has been on plaque accumulation rather than dysbiosis. In fact, clinically the objective of Stage I has been patient’s home plaque reduction rather than finding methods to avoid dysbiosis or diminishing the inflammatory shift of the susceptible host.

Therefore, enabling and empowering patients to successfully control plaque with their own daily habits rose to become the cornerstone of preventive dentistry in general and periodontology and cariology at the forefront.

Empowering the patient

This is one of the most complicated and refined therapeutic goals of periodontology and dentistry in general: bringing a patient who has never been able to manage plaque to a level in which its deposits are scarce and of negligible importance. This goal is rather ambitious as it is the only one which is not based on the core essence of our studies, manual dexterity that is.

Often, however, two common misconceptions prevail within dentistry and dental hygiene.

- The first misconception led clinicians to believe that behavioural changes would be a sole momentum such as a clinical phase monolithically placed prior to the “real” treatment, the one in which hands are used. There is nothing more inappropriate than such an approach. Behavioural changes and plaque control are a continuous endless refinement. A very elegant dance in which the two actors on the stage, the patient and the clinician, are continuously communicating, evolving and readapting based on reciprocal inputs.

- The other fallacy in my opinion is to consider the enabling of the patient to successful plaque control the result of just one single action, or dental examination, in which everything is mixed all at once. To make myself clearer, I would make a parallel to tennis playing, a metaphor which I use most frequently with my students. Imagine that you need to enable a friend to successfully participate in a tennis tournament (needless to say, that the friend of the story has no idea how to play tennis and you have perhaps 2-3 lessons at the most!). What strategies would you adopt? How will you make such a swift and yet effective transformation? I believe any tennis instructor would tell you that the first real question is whether the player really desires to play the tournament at all and if this is not the case, whether a coach may improve its willingness to make the correct changes. Then, and only after that, a real training strategy may be implemented. Nevertheless, without training empowerment, the player will not be able to play even if they are highly motivated.

This is very much the goal of this clinical phase: a clinical objective achievable only with two different, and clearly defined strategies:

- Patient’s motivation creation and enhancement

- Patient’s oral hygiene devices usage skill development

These two clinical phases are interlinked yet completely different in terms of clinical expertise. To fully master this step of the treatment a clinician should be capable of adopting a variety of different gifts encompassing health communication, persuasion and coaching skills, and practical knowledge. I believe that each clinician, be a dentist or a dental hygienist/therapist, should master all these different aspects and understand clearly that the two phases have different objectives and require different approaches.

In a nutshell, if you want your patient to be able to maintain a limited level of dental plaque you need to be able to trigger in them the desire to effectively adopt routine daily dental cleaning practice with the highest level of performance.

The motivation of the patient

Without a motivated patient, the entire periodontology would collapse.

No treatment can be effective if the patient is not motivated. In fact, the absence of an adequate and consistent plaque control would determine the clinical worsening of periodontal conditions to an extent that the treatment per se would actually become detrimental. Non-surgical periodontal treatment proves to be irrelevant if no plaque control is implemented (Ng & Bissada, 1998), pocket-colonising bacteria would return to pre-treatment value within 2 weeks and gingival inflammation within 4 weeks (Magnusson et al., 1984). Interestingly, a clinical session with professional dental cleaning and oral hygiene instruction is equivalent or superior to numerous sessions, without oral hygiene instruction, in terms of control of gingival inflammation (Needleman et al., 2015).

In the case of surgical interventions, the absence of plaque control determined in fact even a significant worsening of the pre-treatment periodontal condition to an extent that it may appear that the surgical intervention has in reality multiplied the speed of the disease (Rosling et al., 1976).

All this evidence constitutes the clinical foundation to support stringent and effective plaque control. The possibility of this happening, rests therefore solely on the patient performing themselves efficacious manoeuvres and this may be possible only when motivation has occurred.

Compliance, adherence and concordance

The interplay and the communication among patient and therapist and the subsequent patient’s behavioural change have been the focus of a significant amount of research.

Terms such as concordance, compliance, and adherence are key terms frequently employed in the context of healthcare to describe how patients engage with prescribed treatments, medical advice, or therapeutic recommendations. These concepts are central to understanding the dynamics between healthcare providers and patients, as they highlight the degree to which individuals follow the guidance necessary for achieving optimal health outcomes. They encompass a range of behaviours, from taking medication as directed to adopting lifestyle changes and maintaining preventive measures.

Although these terms are often used interchangeably, each one of them carries its own distinct meaning and emphasises a different aspect of the patient-care relationship.

Concordance, for instance, reflects a mutual agreement between the patient and the healthcare provider, emphasising collaboration and shared decision-making.

Compliance, on the other hand, traditionally focuses on the extent to which a patient follows the healthcare provider’s directives, often implying a more passive role for the patient.

Adherence builds on this idea but adds a modern perspective, highlighting the patient’s active and voluntary commitment to agreed-upon treatments and lifestyle modifications. Understanding these subtle differences is crucial for fostering effective communication and promoting sustainable health behaviours (Abbinante et al., 2024).

As Jeffrey K. Aronson (Aronson, 2007) explained:

“The word ‘compliance’ comes from the Latin word complire, meaning to fill up and hence to complete an action, transaction, or process and to fulfil a promise. In the Oxford English Dictionary, the relevant definition is ‘The acting in accordance with, or the yielding to a desire, request, condition, direction, etc.; a consenting to act in conformity with; an acceding to; practical assent.’ I have also understood it to mean acting in accordance with advice, in this context advice given by the prescriber, but the modern attitude to the word is that it betrays a paternalistic attitude towards the patient on the prescriber’s part and that it should not be used.”

The term compliance stands for patients following the recommendations provided by healthcare professionals regarding treatment, medication, lifestyle changes, or other aspects of their healthcare regimen. It typically implies a more passive role for the patient, without necessarily being fully engaged in the decision-making process.

Jeffrey K. Aronson (Aronson, 2007) clearly explained adherence: “It comes from the Latin word adhaerere, which means to cling to, keep close, or remain constant. In the OED it is defined as ‘Persistence in a practice or tenet; steady observance or maintenance’, a definition that appropriately conjures up the tenacity that patients need to achieve in sticking to a therapeutic regimen.” The extent to which patients follow the recommended treatment regimen is a crucial factor in managing their health. This concept goes beyond simply observing whether patients follow the doctor’s instructions. It also involves broader aspects. Specifically, it includes both the behavioural aspect, which refers to the actual behaviour of the patient in adhering to the established therapeutic plan, and the attitudinal aspect, which reflects the level of commitment and dedication the patient has towards the defined treatment goals. In other words, it’s not just about carrying out the medical instructions, but also adopting a positive and motivated attitude toward the treatment, with an understanding of the importance of long-term outcomes.

"Concordance" is described as: "Agreement or harmony; accord, harmony." Interestingly, however, another meaning of "compliance" is: "Agreement, harmony; friendly relations between parties," which seems to convey almost the same idea as "concordance." The concept of concordance implies that doctor and patient should work together to decide on the treatment the patient will follow. This approach also suggests that patients should take on greater responsibility for managing their own health, although not everyone is ready or willing to do so. Moreover, there are deeper, even philosophical, reasons that explain why there is currently an imbalance between what is expected of the doctor and what is expected of the patient.

I strongly believe that concordance is the relationship that we are all seeking in contemporary periodontal clinics. In fact, the dynamic of the intertwined relationship among clinicians and patients is a two-way, very much active exchange in which continuous reciprocal adjustments are needed in order to maximise the potential of a complex behavioural change such as the improvement of oral hygiene practices.

Creating concordance

Already in 1979, it was suggested that to achieve a good clinical outcome and an ethical approach that is right and correct, it is necessary to have adequate communication and, at the same time, an increase in the time dedicated to dialogue with patients (Stewart et al., 1979). These two important points lead to an overall improvement in oral health through behavioural change.

An interesting fact is that the average time range for a patient's initial statement in the United States is only 22 seconds, after which the doctor interrupts and asks the questions they want to know. Another study in the field of neurological practice reports that, on average, patients speak for only 1 minute and 40 seconds (Blau, 1989; Marvel et al., 1999).

Patients' stories are frequently interrupted by doctors after just a few seconds, with lists of symptoms accounting for 75% of discussions in this short period of time (Langewitz et al., 2002).

Clearly, the lack of communication and communication skills among health professionals is something that is not only indicated by health literature: as an observer and clinician, I have had the chance to notice throughout my career so far that the time spent “talking” with the patient is often seen as “unproductive”. I strongly believe that there is nothing more irrational and incorrect than such an affirmation. This, I believe, is not just due to the fact that normally this time in the clinic is not perceived as the time in which manual dexterity is employed and therefore self-evaluated as a sort of aperitivo preceding the “real stuff”. It is also quite frequent that clinicians do not receive any formal teaching and study on communication and the potential impact of communication in achieving clinical goals.

Indeed, classic motivating techniques are based on personal and empirical methods. However, there is clearly a potential for clinical failure in those techniques (Ramseier & Suvan, 2014). Allow me to expand on this with some examples. There is a tendency to overvalue the term “instruction” in oral hygiene instruction. As it was stated before, this might be possible if we were to achieve compliance instead of concordance. Thus, a system in which the patient blindly follows the clinician’s directives. Therefore, I have noted that some clinicians would base their motivation system on knowledge (“if I explain to the patient how important plaque control is for their health, the patient would adopt correct strategies”), ability (“if I show and teach the patient how to correctly use an oral hygiene device, they will use it routinely”) or threat (“If I explain to the patient that if they do not brush their teeth, tooth loss and pain will appear”).

As I said before, this is often the case when the two important phases of motivation and skill demonstration are clotted together. I would stress once again that motivation is a delicate and ineffable goal that should be targeted professionally. Thus, to effectively change patient behaviours through an appropriate approach, we can utilise the Motivational Interviewing approach introduced by Miller and Rollnick in 1983.

This approach focuses on strengthening the patient’s intrinsic motivation through an empathetic and non-judgemental relationship, allowing them to explore and resolve their ambivalences. It facilitates change by promoting self-sufficiency and self-efficacy.

There are important and essential skills to uphold. Empathetic ability, which forms the foundation of concordance, involves emotional resonance and understanding the patient’s perspective (Ramseier & Suvan, 2014). However, I would encourage the reader to impress in their mind that this does not come with natural instinct but rather, it is a capability and skill that needs to be acquired through dedicated studies and specialisation.

Creating skills: The oral hygiene paradigm

I believe that the most important skill that we should aim for our patients is the capability to effectively clean interdentally. My conviction is based on one of the classical studies of periodontal literature: the very important study conducted by Axelsson and Lindhe in 1981 (Axelsson & Lindhe, 1981) examining the effect of plaque control on caries and periodontal disease.

A total of 555 patients were divided into a control group (n=180) and a test group (n=375). Members of both groups initially underwent a baseline examination, which included assessments of oral hygiene, gingivitis, periodontal disease, and caries. Subsequently, the control group was seen only once a year for dental cleaning and other sessions were scheduled if symptoms occurred. The test group received cleaning and motivation sessions on a 3/4-month basis. This treatment included education and practice in oral hygiene techniques as well as meticulous prophylaxis. Patients were followed for 6 years and both gingival and plaque levels were recorded in the interdental and bucco-lingual areas.

After 6 years, the control group showed an increase in plaque control in the bucco-lingual areas whereas interdentally, plaque levels obliterated 100% of the areas. Gingival inflammation showed deterioration in both bucco-lingual and interdental areas. That is rather interesting in fact! One might think that if there is a reduction in plaque in the bucco-lingual areas, a consequent reduction of inflammation should follow; instead, bucco-lingual inflammation would also follow interdental plaque accumulation and inflammation. In a nutshell: if a patient shows two papillas inflamed it is very likely that the area in between, even if there is no plaque, would show inflammation.

Conversely, the test group experienced a significant reduction in plaque and gingival inflammation in all areas. Moreover, decays were virtually absent through the 6-year period in this group. Clearly, the data supported the conclusion of the study, rather a clinical dogma to my experience, that is: the maintenance of null or negligible amount of plaque interdentally is the prerequisite to maintain oro-dental health.

Dental floss or interdental brush?

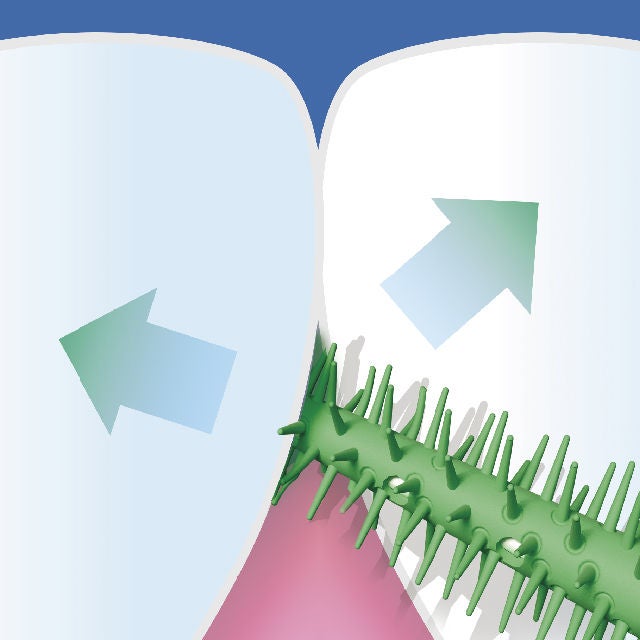

The most used method for plaque control is tooth brushing. However, the most important thing to note is that the toothbrush alone is not able to effectively reach the interproximal areas, especially of the posterior teeth, which are the areas with the highest plaque accumulation (Sjögren et al., 2004). Periodontal diseases and dental caries are more prevalent in these areas (Axelsson et al., 1977), so it is crucial to monitor and control plaque presence effectively.

Dental flossing has always been advocated as the main and effective tool to maintain interdental plaque under control.

According to Warren et al., (Warren & Chater, 1996), research comparing the usage of toothbrushing with flossing has shown no discernible advantages. Furthermore, a recent analysis revealed that self-flossing has little impact in lowering the risk of dental cavities (Hujoel et al., 2006). It is supposed that one of the reasons for the limited efficacy would be that the difficulty in using it makes it less applicable for patients (Fischman, 1997).

In a systematic review, 11 studies were evaluated regarding the effectiveness of dental floss in addition to tooth brushing compared to tooth brushing alone in the context of plaque and gingival inflammation. It was observed that only 3 out of the 11 studies demonstrated a significant reduction in plaque index when dental floss was used alongside tooth brushing.

However, for gingival score and bleeding score, only 1 group out of the 11 studies found that the use of dental floss together with tooth brushing was effective (Berchier et al., 2008). It might be argued that flossing requires dexterity and expertise yet, notably, 3 out of the 8 studies which did not support the usage of interdental flossing were in fact conducted on dental and dental hygiene students who should know at least flossing technique (I must confess, however, that I examined countless colleagues in my professional career and I rarely noticed a higher plaque control than in the non-professional population…yet this is another story).

Hujoel and coworkers (Hujoel et al., 2006) conducted a systematic review in which they examined 6 studies involving a total of 808 children aged between 4 and 13 years old. It was suggested that dental floss is effective in reducing interproximal caries by 40% only when performed by a dental professional five times a week, that is obviously an impossible cleaning suggestion. Furthermore, it was observed that neither professional flossing performed every three months for three years nor independent flossing in young adolescents for two years reduced the risk of caries.

Taking into account this evidence altogether, it appears that routine usage of dental flossing should not be recommended due to its lack of efficacy. Moreover, clinical experience indicates that the number of clinical sessions needed to achieve proficiency in the usage of floss may lead to rather excruciating and disappointing long sessions. It is therefore not with surprise that the current guidelines do not support the usage of interdental floss as the first choice in patients with periodontitis (Sanz et al., 2020).

Conversely, interdental brushes appear more effective and simpler to use. In a systematic review, Slot et al. (Slot et al., 2008) examined 9 studies and concluded that the use of interdental brushes (IDB) removes more plaque than tooth brushing alone. The studies showed a positive and significant difference in the use of interdental brushes compared to plaque index, bleeding index, and pocket depth. In this review, 5 out of 8 studies found that the use of interdental brushes was more effective than dental floss. Additionally, 2 out of 3 studies concluded that using interdental brushes along with tooth brushing significantly reduced plaque and bleeding indices compared to tooth brushing alone.

A randomised clinical trial conducted by our group evaluated the use of home oral hygiene aids in young patients with intact papillae (Graziani et al., 2018). We found that instruction on home oral hygiene, focusing on proper and regular brushing techniques, significantly reduced the plaque index in young patients with intact papillae. This confirmed that the use of interdental brushes provides greater benefits by reducing interdental plaque accumulation. Moreover, the group using floss did not demonstrate any additional benefit compared to those using toothbrushing exclusively.

Despite a significant reduction in plaque following regular brushing, the interdental area remains a critical point for maintaining gingival health. The use of dental floss does not lead to a significant reduction in general or interdental plaque, even among dental students, who are expected to have greater knowledge about the correct use of floss and the importance of home oral hygiene. It is evident that the use of interdental brushes is highly effective for controlling and removing interdental plaque.

Interdental rubber picks

Our group demonstrated that using a toothbrush alone or in combination with interdental devices is effective in reducing plaque levels and, consequently, inflammation in periodontal patients.

Interdental brushes and interdental picks showed significantly greater efficiency in plaque removal and gingival inflammation reduction compared to brushing alone or brushing combined with flossing. This study demonstrated that interdental brushes and rubber interdental picks are equally effective (Gennai et al., 2022).

Even in young individuals with intact periodontium, a study confirmed the efficacy of interdental brushes and interdental picks compared to brushing alone. In subjects who used interdental picks, a significant improvement in interdental inflammation was observed compared to those who used only dental floss (Graziani et al., 2018).

The importance of these findings lies in the fact that data were analysed using two different models based on the integrity of the papillary structure. As such, data were available for both intact papillae and periodontitis patients. This provides a comprehensive insight into the performance of devices for interdental cleaning.

Article written by Filippo Graziani, DDS, PhD, Professor of Periodontology at the University of Pisa, Italy, and Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Disclaimer: The links, images, and bold formatting included in this article were added by SUNSTAR and do not reflect the views or involvement of the author. These elements may refer to commercial content with which the author is not affiliated.