Periodontitis and Its Impact on Patients’ Lives

Article written by Filippo Graziani, DDS, PhD, Professor of Periodontology at the University of Pisa, Italy, and Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Introduction: Health and quality of life

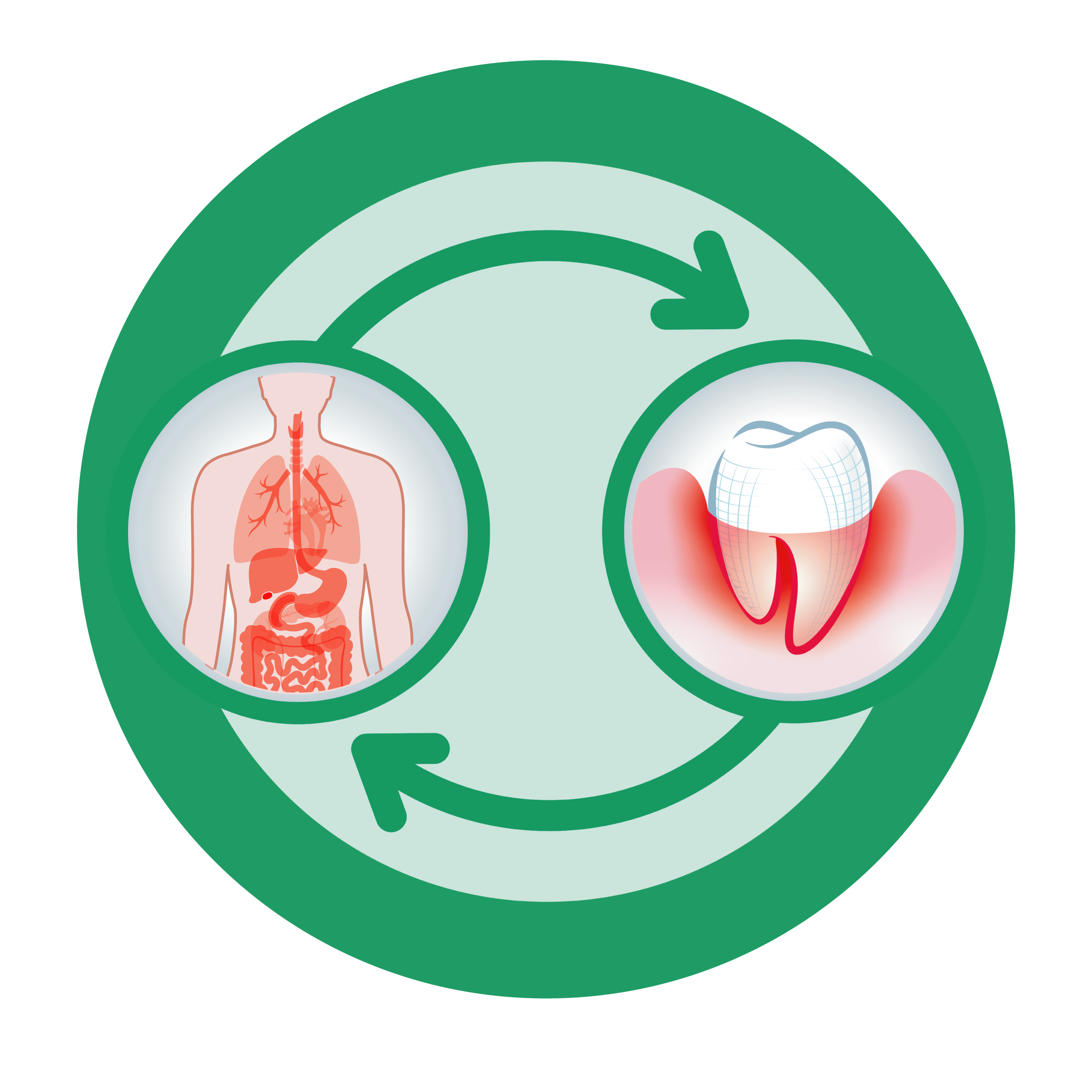

Our research group has focused for the last 15 years mainly on understanding the effects of treatment of periodontitis upon other outcomes compared to the ones that are classically studied within the dental field. In particular, the effects that are beyond the actual parameters taken in the oral cavity, have been one of our consistent interests.

Indeed, oral health is a fundamental aspect of overall well-being, influencing not only dentition and its functions but also the medical, psychological and social dimensions of patients’ life.

Health is defined as "a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" (Grad, 2002).

All the dimensions that are aligned with oral health - i.e. talking, chewing, eating swallowing, smiling, kissing to name a few – are often intertwined and influenced by a multitude of characteristics that are not confined to the oral cavity per se. This melting pot of functions and activities are fundamental for each human being’s life and for the one of the most important features of humans: the capability to connect among each other.

Overall, our entire existence is densely shaped through our capability to appreciate life in general and to manifest a high quality of life. The World Health Organization has described quality of life as “individuals' perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” (Power & Kuyken, 1998). Quality of life has a significant impact on “the extent to which a person enjoys the important possibilities of life while maintaining well-being” (Locker & Allen, 2007).

This concept is particularly relevant in the management of periodontal diseases that profoundly affect patients' daily lives, both physically and psychologically, as well as socially.

Impact of periodontitis on patients’ lives: its perception and how it affects quality of life

The impact of a disease on the life of a human being is multifaceted and extremely subjective. This is even more pronounced for periodontitis due to the elusiveness of the disease in terms of perceived symptoms.

Our research group studied the impact of the disease on 240 patients affected by periodontitis to find that periodontitis is often not perceived as a disease. In fact, only 15% of the patients had virtually no symptoms; however the vast majority of the patients did not perceive these as “symptoms”: in a nutshell, for a patient, occasional bleeding gums (nearly 50% of the cases) or bad breath (40% of the population) were not associated with the chance to have a disease but just temporary fluctuations (Discepoli et al., 2015).

Further, once the patient is made aware of their gum disease, recurrent feelings are the one of fear (“will I lose my teeth?”), shame (avoidance of food, people, covering the mouth with their hands while smiling) and anger (“why didn’t the dentist say anything before?”) (Abrahamsson et al., 2008). The latter, I must say, is something that I often witness in the patients referred to my clinic, as patients feel betrayed and let down: I personally believe that the interruption of a relationship based on trust is the highest “sin” within professional dentistry.

Clearly, periodontal disease affects life in general and the perception of its quality. Normally, in clinical practice, periodontal health status is measured and monitored through oral parameters such as clinical attachment level, bleeding on probing, probing depth, recession, and plaque values. While these parameters are crucial for defining periodontal health vs. disease and to monitor the performance of the treatment, it is equally important to understand and to measure the impact of the disease on a patient’s overall life and to target this to ensure a tangible improvement for the patient (Black, 2013).

The understanding of the fact that quality of life is affected by oral conditions imposes to research to comprehend this dimension thoroughly. Even more in this case, in which research has an immediate impact not only on patients’ lives but also on clinicians’ capability to intercept a professional opportunity. Capturing such undefined dimension proved to be quite complex and several tools have been introduced to evaluate the quality of life related to oral health in patients, including those with periodontal diseases. These tools measure the impact of the disease on the patient’s quality of life, their perception of the condition, and the effects of treatment through questionnaires and scales. Psychometric scales have the objective in facts to measure area and characteristics that are normally vague and not directly transferable in measures.

Questionnaires, in particular, support clinicians to better understand the effects of the disease and its treatment on symptoms, psychosocial factors, and patient satisfaction (Locker & Allen, 2007; Wyrwich et al., 2013). This also facilitates the clinical decision-making process, enabling the provision of more personalized care for each patient (Black, 2013). On the other hand, such questionnaires are not necessarily related with one single disease of the patient’s mouth. In fact, disease-specific questionnaires are not available as the dimensions that may be touched by edentulism may overlap the ones determined by periodontitis. Furthermore, these outcomes are profoundly saturated with personal values, vagueness and subjectiveness as they refer to a rather personal and ineffable dimension.

When measured through specific questionnaires, patients with periodontitis show a lower oral health-related quality of life compared to individuals without periodontitis, and this association also depends on the severity and extent of the disease.

Greater severity and extent of the disease lead to a worse oral health-related quality of life (Al Habashneh et al., 2012; Brennan et al., 2007; He et al., 2018; Jansson et al., 2014; Meusel et al., 2015; Mulligan et al., 2008; Needleman et al., 2004; Palma et al., 2013; Saletu et al., 2005). Even in young patients with periodontitis, a lower oral health-related quality of life has been observed (Carvalho et al., 2015; Eltas & Uslu, 2013; Llanos et al., 2018; O’Dowd et al., 2010).

The reason for such an impact is diverse and touches different aspect of the patient capturing not only aesthetic and function, but also psychological and social aspects.

First and foremost, symptoms of the disease are crucial and affecting in a dose-dependent response quality of life. Swollen, painful gums, gum recession, halitosis, and loose teeth are important symptoms of periodontal disease that may profoundly affect the physical, social, and psychological aspects of a patient's quality of life. Periodontal patients have reported that these symptoms negatively impact their self-esteem, appearance, comfort, and even their masticatory function (Needleman et al., 2004).

Furthermore, periodontitis is one of the leading causes of tooth loss, with a significant impact on nutrition, aesthetics, and systemic health. The loss of posterior teeth, very common indeed in individuals with periodontitis, reduces the efficiency of masticatory function, leading patients to adopt an improper diet with lower nutritional intake (Blanchet et al., 2008; Kosaka et al., 2014, Gennai et al. 2021). Further, tooth loss can also result in malocclusion, increasing the likelihood of temporomandibular disorders in patients with periodontitis (Sheiham et al., 2011). The loss of anterior teeth compromises the phonetic function of individuals and results in an unpleasant aesthetic appearance for patients (Antoniazzi et al., 2017). Indeed, the replacement of missing teeth, whether posterior or anterior, overall leads to improvements in both the social and personal aspects of patients' lives (Craddock, 2009).

Aesthetic is an important aspect of social dimension and self-worth appreciation. Patients with periodontitis tend to cover their mouth when they laugh and showing a less open smile in general (Patel et al., 2008). In other words, the greater the number of periodontal pockets, the less frequent the smiles of periodontal patients. Periodontitis, due to the greater involvement of systemic inflammatory factors and an increase in psychosocial impacts, leads to a decrease in self-esteem and socialization (Needleman et al., 2004; Paraskevas et al., 2008). Indeed 90% of the patients feel that oral health had a significant impact on their lives (Needleman et al., 2004).

The psyche of the periodontitis-affected patient and role of stress

Classically, Hans Selye defined stress as "a non specific response of the body to any demand placed upon it" and classified it as acute or chronic depending on the duration of the stressful event (Saturday & Selye, 1950). Nowadays, it is clear that stress-related diseases are ubiquitous, and that stress plays a significant role in the vast majority of the non-communicable diseases. Stress is an alteration of allostasis (the ability to successfully adapt to changing environments). When the challenges are chronic and frequently beyond the normal ranges of adaptive responses, allostatic load accumulates, and stress may appear.

Chronic stress is linked to periodontal disease (Decker et al., 2021; Dumitrescu, 2016). Stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of necrotizing periodontal disease (Coppola et al., 2019; Herrera et al., 2018). This correlation was also demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an increase in both necrotizing periodontal lesions (Ammar et al., 2020; Aragoneses et al., 2021; Di Spirito et al., 2021; Iannelli et al., 2020; Martina et al., 2020) and oral mucosal lesions. The explanation lies in the significantly higher stress levels observed compared to the pre-pandemic period (Barzilay et al., 2020; Kannampallil et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2021).

The mechanism behind this association is complex and deserves further explanation in order to capture the granularity of this liaison. Overall, stress alters patient’s susceptibility to the diseases through direct and indirect mechanisms (Boyapati & Wang, 2007).

Firstly, subjects that are under significant stress tend to look after themselves less and therefore usually adopt more unhealthy behaviours. Thus, subjects will adopt risky health behaviours such as tobacco use, a significant risk factor for periodontitis (Costa & Cota, 2019), alcohol consumption, a risk factor for tooth loss (Copeland et al., 2004), and unhealthy diets that promote dysbiosis and foster inflammation (Foster et al., 2017).

This is not just the result of an unhealthy coping mechanisms but also the result of adaptive physical changes, such as stress-induced alterations in hippocampal morphology, that may also lead to behavioural modifications, including hygiene practices, anxiety, and treatment compliance (Decker et al., 2021). Interestingly, when stress increases, subjects tend to look less after their health and in particular oral health. Indeed, individuals experiencing work-related stress or working in high-pressure environments tend to have higher levels of plaque due to reduced personal care and irregular oral hygiene practices, resulting in poorer oral health-related quality of life (Abegg et al., 1999). Behavioural changes, during both the active and maintenance phases, have been implicated in the onset (Dumitrescu, 2016) and progression (Genco et al., 1998) of periodontitis, and increased tooth loss (Anttila et al., 2001). Prolonged periods of stress increase behaviours such as smoking, drinking, and irregular sleep, which heighten susceptibility to periodontitis (Borrell & Crawford, 2011). Moreover, stress can alter the composition of the oral microbiome, leading to stress-induced dysbiosis (Guret al., 2015). Various studies have shown that dysbiosis can cause diseases, (Barone et al., 2020; Duran-Pinedo et al., 2018) such as periodontal disease, which is characterized by a dysbiotic microbiota.

Therefore, briefly, when one is stressed, behaviours and plaque accumulation characteristics will modify to an extent that would make the subjects more prone to develop periodontitis.

Further, stress activate directly two important mechanisms which are more direct in nature. Firstly, an allostatic load may trigger the production of Corticotropin Realising Hormone (CRH) in the hypothalamus, that in turn will trigger the pituitary gland to release Adrenocorticotropic hormone that will reach the suprarenal cortex to release Cortisol. Accordingly, high cortisol levels were detected in the crevicular fluid of periodontal patients (Rai et al., 2011). Cortisol would eventually determine enhancement of glucose levels, and cytokines levels creating overall immunodepression and enhancement of inflammation. It is known that stress can indirectly promote the onset and worsening of infections by increasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to mild chronic inflammation (Duran-Pinedo et al., 2018).

Furthermore, after the experimental addition of cortisol, an increase in periodontal Fusobacteria species was observed, suggesting that the periodontal microbiome is capable of sensing stress-induced changes (Duran-Pinedo et al., 2014; Yost et al., 2015). This alteration also triggers the autonomous nervous system that would act on the suprarenal medullae resulting in the production of epinephrine that would also act on the overall level of inflammation.

Indeed, a classical study from the Genco’s group identified a higher salivary production of cortisol in subjects with periodontitis and high level of financial stress compared to the ones with lower level of stress (Genco et al., 1998). Interestingly, financial strain-derived stress has been associated proportionally to loss of periodontal attachment: the more you stress about money and the more likely you are to have periodontitis (Ng & Leung, 2006).

Therefore, when a subject is stressed, more plaque would accumulate. Furthermore, it is likely that if the subject is a smoker, the tobacco consumption will enhance, and further alteration of the inflammation will occur as more cortisol and epinephrine will be produced. Overall, these mechanisms translate with higher tendency to develop periodontitis.

Interestingly, patients who underwent periodontal treatment with strategies to reduce stress and anxiety experienced less post-operative pain compared to those who received only periodontal treatment (Kloostra et al., 2007). A study demonstrated that periodontal treatment combined with yoga was associated with a significant decrease in stress levels and a greater reduction in probing depth compared to standard treatment (Sudhanshu et al., 2017). It was also observed that, in terms of healing, patients who underwent pre-operative relaxation techniques experienced significantly better wound healing compared to those who did not receive such techniques (Feeney, 2004). This aligns with a study suggesting that stress can negatively alter the immune response, leading to delayed healing of periodontal wounds (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1995).

Periodontal treatment and improvement of oral health-related quality of life

The management of periodontitis thus provides benefits that goes beyond the life of the individual affected (Chapple, 2014b; Papapanou et al., 2018b; Tonetti et al., 2017).

A study demonstrated that periodontal treatment has a significant impact on oral health-related quality of life (Ozcelik et al., 2007). Another interesting study concluded that the type of instrumentation does not affect the improvement in oral health-related quality of life in periodontal patients after non-surgical treatment (Shanbhag et al., 2012). Most importantly, the vast amount of post-treatment benefits are perceived after non-surgical treatment, as surgical treatment does not provide any change in the perception as it can be easily imagined due to the limited localization of the surgical area. This is expected as localized forms of periodontitis do not affect significantly oral health related quality of life compared to the generalized ones (Llanos et al., 2018).

Gingivitis and oral health-related quality of life

Interestingly, alterations of oral health-related quality of life are already evident early on in cases of gingivitis. A study conducted on a population of 1.874 adolescents demonstrated that gingivitis has a negative impact on oral health-related quality of life (Krisdapong et al., 2012). This result is consistent with a similar study conducted in Brazil on 1.134 adolescents (Tomazoni et al., 2014), patients with gingivitis showed a significant improvement in oral health-related quality of life after treatment (Cortelli et al., 2018; Goel & Baral, 2017). Our group found that on a sample of 140 patients affected by generalized gingivitis, intensive treatment determines important amelioration as its resolution reduces gingival inflammation and plaque levels, as well as systemic inflammatory markers and determines an improvement of quality of life (Perić et al., 2022).

Article written by Filippo Graziani, DDS, PhD, Professor of Periodontology at the University of Pisa, Italy, and Honorary Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Disclaimer: The links, images, and bold formatting included in this article were added by SUNSTAR and do not reflect the views or involvement of the author. These elements may refer to commercial content with which the author is not affiliated.